01.08.2012

Luda Express or the laboratory of greed deedsLUDA EXPRESS (Or, the Laboratory of Great Deeds)

In Petersburg, there is now a new powerhouse – New Holland. Once the city's most tantalizing and enigmatic terra incognita, seen only through teasing glimpses of the alluringly empty space under the romantic arch crowning the canal where the thick brick walls turn in towards the island, now it chastens those glances with an emptiness that is no longer metaphysical, but based on what is physically there in the day-to-day life on the island. This emptiness, however, bristles with an electric anticipation; after all, much has been promised (as always), and these promises paint the picture of yet another grandiose futurist enterprise for Petersburg.* [*The name of the island itself speaks to the ambitions of Peter the Great, who thought of the part of Russia along the banks of the Neva as a New Europe, and Petersburg its port city.]

This humble project before us now is but a laboratory of the future project, whose actual contours are still forming.

While the anticipation is pleasant enough in and of itself, it should be said that the time for reckless promises and grand illusions has passed, and the time has come for the growth of the market and some strategic management. In other words, we need do-ers, who can take a serious look at the situation and, most importantly, who can implement whatever solutions prescribed with clarity, efficiency, and a precise idea of format and objectives.

For the last ten years, the contemporary art in Petersburg has firmly entrenched itself within its gallery space, becoming not only a rooted phenomenon with its own legal residence, but also staking claims towards the development of new territories – as first evidenced by the emergences of lofts – with former industrial buildings now outfitted as centers of cultural activity.

What is truly unique about New Holland is that here, we find nothing of the trappings of the galleries or loft spaces. Instead, what we have before us is a clean slate in a beautiful, antique frame. Or maybe, it's the opposite: a new beginning, the “zero degree” so coveted by Suprematism.

It is from this blank page that the art of St Petersburg can try to start anew. For this purpose, it has even been given a temporary container – a veteran wagon from the “agit-train revolution,” or maybe an unsullied office space.

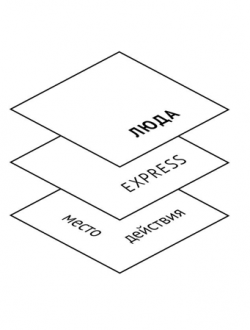

Peter Belyi’s “laboratory of great deeds,” “Lyuda EXPRESS,” is ideal for the current situation in that it takes a form that corresponds directly to public expectation. The idea is simple: the space works non-stop forf two weeks, with a new exhibition opening every three days. Five solo exhibitions will be summed up by a collective group show. The intimate format will encourage minimalism and precision, while the rapid succession of exhibitions lends density to the activity and pacing.

Belyi has previously undertaken a similar endeavor. Two years ago, he carried out an unprecedented experiment, opening the Lyuda Gallery in a tiny, whitewashed room off one of the courtyards on Mokhovaya Street. For ten months, a new exhibition would open every week, and Lyuda quickly started making headlines within the St Petersburg art world. The result was a fairly accurate blitz-portrait of contemporary art in Petersburg, in a non-profit space where artists were free to test out pure expression.

For the last decade, it is as if the art of Petersburg has sacrificed its particular character, dissolving into the general Russian – or, more specifically, Moscow – context. Belyi is committed to the idea of representing this art as its own independent, evolving phenomenon. The last attempt at branding Petersburg art – Timur Novikov’s Neoacademism – is already a thing of the past, and while the last decades of the 21st century yielded more than a few new talents, any dominant or definitive conception of what constitutes mainstream culture for the city has yet to be established. These days as a rule, any promising young artist must make his or her start in Moscow, immediately diving right in to the intensity of city life.

It’s true, there are some exceptions. Just a few years ago, having been fed up and disillusioned with Moscow’s “vanity of vanities,” Pavel Pepperstein suddenly decided to move to Petersburg, while Marat Guelman opted to find a center of contemporary art in Perm, bringing practically his whole sphere of activity with him to the provinces.

As it is, what Belyi sees in St Petersburg is not what lies on the surface, but instead an organic part of the internal workings of the city, her inimitable folds, where art is not institutionalized, not just “the next project.” “The real life of the city is traditionally concentrated in its attics and basements,” Belyi observes. “This is an inescapable feature of Petersburg. Perhaps some might see this as a symptom of marginality, the evidence of the deep periphery of the local scene. And they will probably be right.”

Art, after all, does not depend on the presence of the market or prestigious international forums; it does not depend on the success of artists or galleries nor the many other requisite institutional factors, indicating prosperity. Contemporary art in Russia is almost standardized, or at least, it has long since been formalized in the institutional sense of the word, becoming quite commonplace and even conventional. One could even speak about this project of “contemporary art” in the past tense, as something that has already happened, since twenty years is considered a sufficient period of time to judge something as a historical phenomenon.

“Luda EXPRESS” offers its audience a rather unusual artist roster: Konstantin Simun, Alexander Morozov, Kirill Khrustalev, Vlad Kulkov, and the Mylo (“Soap”) Group (Semyon Motolyanets, Dmitry Petukhov). These artists come from different generations, and the connection between them may at first seem arbitrary, but there is something similar inherent in the type of creative activity they practice. It is the divergence from the straight path, the character of contemplation and of minimalism, not as a definitive direction, but as a particular relationship to form.

A patriarch of home-grown minimalism, Konstantin Simun is revered as the artist behind The Broken Ring, the memorial to the Leningrad blockade on the Road of Life. The acute clarity, austerity and formality of the artist’s statement may reflect the style of the times, but, above all the ideological or symbolic investment, the monument’s form nods to the minimalist abstraction of the 1960s. Two arms of an open arch create a kind of portal, framing the view of the Road of Life leading to Lake Ladoga. This arch brackets the horizon line between the sky and the water, in a rhythm which strangely echoes New Holland, an island whose cape is re-interpreted by the artist as the bow of a ship, the Determined Peter the Great, looking off to Europe.

Simun’s latest works, featured in the exhibition “Apocalypse,” comprise a series of found objects photographed in their natural settings: white plastic canisters in the sands of a shoreline, as if beached by the sea. The extent to which they are actually “found” is debatable. Before us are the artist’s sculptures, the canisters carved with knives so as to resemble human heads, suggesting the mute witness of a vanished civilization. It is no coincidence that they call to mind the Easter Island statues, or the sculptures of the Indians of Central America, with the plasticity that so influenced the development of Modernist forms of the 20th century. The encounter of these choppy, lapidary forms amid the smooth, designer outlines of the mass-produced commodity good is its own little game, all in keeping with the spirit of found art: it exists where the keen eye of the artist finds it.

This kind of clever play with garbage, with objects whose existence is almost predetermined for disposal, serves as one of the foundations for the work of Kirill Khrustalev, whose recent emergence on the St Petersburg art scene has been heralded as a real discovery. His work resurrects the spirit of Oberiu conceptualism, where the intersection-juxtaposition of one word-object with another strikes sparks of wit, revealing its pure essence.

Khrustalev works with whatever bits of everyday life are at hand, trinkets most trivial and miserable in their mediocrity: beer tabs, cigarettes, napkins, candy, coins, cups, stones, matches, drops of coffee on a piece of paper, exploded bits of balloon… In the ambitious, aphoristic titles assigned by the artist (this exhibition – “Momento vita” – being no exception), these things, or, more precisely, these already-no-longer-things, which have lost their former value and have become, from an everyday point of view, trash, are now imbued with new life and depth of a human dimension. In addition to the conceptual level, these works also operate within a formal understanding, as the objects can alternately be read as pure abstract forms.

The exhibition “Factum” features the abstract and minimalist neon cosmograms of Alexander Morozov spectacularly lit against a black wall. If one did not know the esoteric and mystical subtext of these works, one might think they were standing before the austere, linear drafting forms punctuating the Constructivist drawings of Alexander Rodchenko’s Linearism series, or maybe the objects of American Minimalist Dan Flavin. The point, however, lies not in these analogies, but in the actual effect of the translation of these fate-lines into abstract graphic symbols, as well as in the selection of names hidden within them: Victor Tsoi, Marcel Duchamp, Andrei Monastyrski, and Victor Pivovarov.

Primarily a painter, recently Morozov has been drawn to more concise formulas, as demonstrated by his “halos,” heavy horseshoe shapes cast from black rolled steel, whose outlines were taken from 15th century Russian icons. “Captured” at the base of thin, shining neon tubes, they create the effect of a closed circulation of poles and light, the materialization of a miracle of a sacred nature. In this way, Morozov investigates the border between the delicate states of matter and the spirit, seeking materials and forms that can best express and experience the conditions of transition.

Vlad Kulkov creates swirling, intertwining skeins of endless lines, signifying a completely different type of language – that of the tongue-tied shaman or the infantile graffitist, the baby – within the chaotic tangle of lines. In these painterly forms there is something of the organic poetry of the movement of wind, or clouds, water or even lava. They are natural and indisputable, filled with the strength of the self-organizing flow of life, which leaves its traces in the whimsical “Baroque” windings and strokes.

The exorbitance in the subconscious plan of these meandering forms is revealed in the “surrealist” reverse of Kulkov’s abstraction, the full-on expressionism, in which the artist’s language gravitates towards poetic hieroglyphs, like those mysterious markings on the Veil of Maya, masks or disguises of an immense emptiness.

The artist chose to title this exhibition “Rebus,” endowing it with the anagrammatic character of a message, that encourages free association in the deciphering of individual symbols. In contrast to the artist’s previous work, these recent canvases contain stricter, more sharply defined forms, whose needle-like rays are borrowed from Mikhail Larionov’s Rayonism.

Neither Kulkov nor the Mylo Group are suffering from want of attention from the art community. This is not saying anything against these artists. Quite the contrary. In their work one can read a desire to escape the media and publicity organs. For example, Kulkov has spent some time in Mexico, exploring the cultures of the Aztecs and Mayans, while Motolyanets and Petukhov use their actions to take on different shapes and gestures of escapism, obviously drawing from hagiographic texts.

This time they play off their own recent performance in the Museum of Hygiene, when the artists appeared dressed as Saint Stolpniks (complete with halos attached to their heads) around a huge dog - “the predatory hyena.” The title of the action – Give Us A Chance to Do What We Want to Do and Think About What We Want to Think About – unambiguously refers to the contemporary social situation in a country where a prohibitive spirit once more prevails.

The exhibition space will feature the drawings of Petukhov and the folding, carved wooden phrases of Motolyanets, whose cursive font recalls Soviet signage. The artists themselves will sit on the roof, but they will no longer be dressed as the canonized saints, and they will shout into a megaphone phrases taken entirely out of context. They will be accompanied by the same stuffed dog that was with them in the Museum of Hygiene.

Religious subject matter in contemporary art now seems to be all the rage, with myriad artists appropriating Orthodox iconography, canons, and rituals, and applying them to various relevant semantic contexts. With Mylo, there is no mockery, no snark, no speculative imitation, kitsch, nor vulgarity. Their primary objective derives from an exclusively artistic character, where “wit” does not sully the “sublime,” and vice versa.

“Luda EXPRESS” may not set its sights on global order, but it nevertheless manages to uncover the thriving art of St Petersburg, even if the ranks are now made up of artists of different ages and even eras: the Soviet sixties, Post Soviet romanticism, New Russian cynicism, and contemporary obliviousness, in which an independent personal position commands respect and trust.

A line of resistance – what else is left?

Gleb Ershov

|